For the past 20 years, while living and working with computers, we’ve been talking and writing about a time in the future when the transforming trends of the Information Age finally would overcome the Industrial ones. Once, our refrain was that the network is the natural form of human organization for the 21st century. That time has come. We’ve been swirled through this epochal portal as a global society like millions of butterflies caught in the same net.

In the big picture, this is humanity’s fourth great socioeconomic-technological threshold. We’re now zooming up the steep climb of an accelerating paradigm shift completing its transformation, a moment that is a century in the coming.

The seeds of the newest age are planted in the scientific revolution initiated at the turn of the 20th century. Relativity and quantum theory challenge the prevailing reductionist and materialist view of Newton, laying the foundation for new perspectives on reality.

Gestating for a half-century, the birth of the new age literally explodes into public view in 1945. In six short months, the world witnessed activation of the first digital computer, ENIAC, the dropping of atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the signing of the United Nations charter in San Francisco, California. But the Industrial hierarchical-bureaucratic world held sway nearly to century’s end—even as the powerful forces of change ripened and grew.

Now we are fully moved into the Information Age. So it’s showdown time for us in learning these new ways to work. We each personally have no choice but to grapple with the difficult issues raised by the radical restructuring of human reality as a whole.

Virtual teaming is a 21st-century survival skill.

Each age produces a new variation on the ancient theme of “teams," Chapter 3. At a basic daily level, we all live in small groups that become teams when the purpose is task-oriented. Virtual teams cross boundaries of space, time, and organization using technology to extend human capabilities, which gives them uniquely new features.

Successful collaborative work requires "90% people and 10% technology." What works can be boiled down to one word: Trust, which is the topic of Chapter 4. One story we tell there shows how real and enduring this quality is: It begins a thousand years ago. Today, the long-term benefits of great teamwork accumulate as social capital.

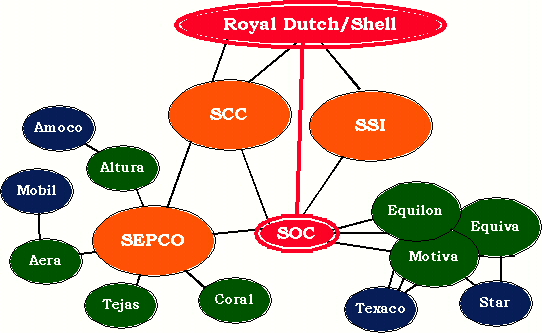

The oil industry is simply a network of enterprise and government-level virtual teams. There is likely not an exploration underway anywhere in the world that doesn’t involve more than one company that is always negotiating with at least one, if not several, governments, whose product is moved, refined, and distributed by at least a dozen more firms. Royal Dutch/Shell Group, of which the Houston, Texas, Shell of this story is just a part, maintains more than 1000 joint ventures.

In 1991, Shell Oil Company sees the worst performance in its nearly century-long existence. Suddenly while Shell is looking backward, the world around it soars ahead. Showing just $21 million in net profits against its more than $22 billion in assets, Shell gets its “wake-up call” that year, says Linda Pierce, a 33-year Shell employee who rose to senior ranks of the company. “We realized that our failure actually began much earlier when large investment decisions were being made at the very top of the company without a system, structure, or process for tapping into the knowledge of the organization.”

For a century, the “majors”–Shell, Exxon, Texaco, and the like—have dominated the industry. In a few years’ time during the 1980s, upstart companies, some with only a handful of employees, begin to exploit cracks in the majors’ business models. The singular world that Shell once ruled with only a few other competitors abruptly crowds with unlikely opponents. The competitive sky is turning colors that Shell cannot even name.

First dozens and then hundreds of companies offer products and services along the whole value chain—exploration, production, chemicals, distribution, and retail. In the new oil business, services prove more profitable than the natural resource itself. Consider Landmark Graphics, now owned by Halliburton. It grew its 1984 computer-aided exploration software to fill 90 percent of the oil-exploration information-technology market in just a few years.1

Shell’s initial response is predictable: Work force reductions of one-third, from 33,000 to 22,00, along with the elimination of significant layers of middle management. “We looked very hard at cost-cutting, which got us in touch with what our competition was doing. Much to our surprise, we learned that we were not competitive in producing a barrel of oil,” Pierce says.

In 1993, Shell’s then-vice president of administration and finance, Phil Carroll, takes over as CEO. Within a few months, Carroll and a coterie of talented people, including Pierce, initiate what comes to be known as “The Transformation,” a radical redesign of the way the company operates. Their new vision is quite simple: To become the premier company in the United States. Soon, imagined covers of Fortune appear around the company, with the pictures Shell executives captioned by that phrase.

The changes to come are profound. Carroll reorganizes the company’s top executives into a “Leadership Council” that replaces the existing three-person General Executive Office. This seemingly simple modification heralds a dramatic break with Shell's organizational history. Shell had been the classic hierarchy with decisions made privately at the top, then imposed downward through a slow-moving, inflexible, not-very-street-smart bureaucracy.

“We knew that an engaged workforce more fully involved in the business of the company would require a different kind of leadership,” Pierce says. “We had technical leadership but not business leadership.” The idea is that in the new Shell, no single place in the organization makes business decisions; many would.

Each principal business (exploration and production, chemicals, oil products) would be run by a chief executive officer responsible for delivering strategy and fulfilling financial commitments. Each also would have its own board of directors with seats held by executives from other internal businesses and corporate functions.

Soon thereafter, the 200 most senior leaders from across Shell convene as the “Corporate Leadership Group,” threading still more connections across the company. Their charge is to protect both the welfare of the whole company and their own businesses simultaneously.

This new business model sends profit and loss to the major businesses, which in turn spawn a rich network of relationships among the company’s financial officers. At one point, the chief financial officer of Shell Oil Company, the corporate “holding company” center of all the businesses, sits on 17 boards.

The Transformation also opens Shell’s doors to the outside. Scores of creative people—authors, consultants, thinkers, musicians, “graphic facilitators”2 and of course industry experts—come through the Shell Learning Center. Carroll builds the facility as an adjunct to the famous conference center at The Woodlands, the planned community outside Houston. The Learning Center is booked all the time but no desks are in sight (except in the offices of the people running the place). Abundant instead are chairs on rolling casters, comfortable enough for day-long meetings, walls that you can pin anything to, flip-charts, projectors, computers for logging into the company’s network—and buffets of excellent food. It’s a superb environment for learning and building trust.

The Learning Center also serves as the meeting place for the company’s many initiatives. Each initiative involves posing a set of questions to a cross-section of Shell employees. Typically these people would devote mixtures of full and part-time to the initiative for as long as six months. By its conclusion, Shell would have a new approach to diversity, recognition and strategic cost leadership.

In October 1997, Shell’s planners, a small group of future-attuned strategists, many of whom have first-hand experience producing oil, present a startling statistic to the Leadership Council at its annual retreat in Galveston. As recently as three years earlier, Shell had owned nearly 100% of the companies in which its assets were deployed. By the time of the October meeting, that number has sunk to 34%. Everything else is or soon would be in joint ventures with competitors (including its retail business with Texaco and Saudi Aramco), or in global alliances with its parent (Figure 2.1). The planners predict the number will plummet even lower when Royal Dutch/Shell turns all of its businesses into global ones. The conclusion is that Shell no longer stands alone; it is deeply enmeshed in a “networked community” whose rules, assumptions, and guiding principles diverge markedly from its previous architecture.

Shell moves from “control through ownership to influence through relationships.”3

A month later the Leadership Council convenes 38 people to join them as part of a new group of Strategic Initiative Teams (SIT). A broad cross-section of employees—from Chet Servance, a boiler-maker at the company’s Deer Park Refinery, to the company’s then-treasurer, Tom Botts, are invited. Their mission is to answer four fundamental questions about the new Shell and make recommendations that the company can act on immediately:

How will we learn?

What will it mean to be part of the Shell family?

How will we develop our people?

How will we govern?

They divide into four teams, with the Leadership Council addressing the fourth question on governance. Pierce calls it the best project she ever worked on. “They started as four teams and ended as one,” she says. “It began with the Leadership Council’s desires but ultimately what drove the team was what they came to believe was important. That happened in a workshop [at the Learning Center] where the team became one and took over the design of workshop much to delight of the facilitators who had designed it!” Pierce is referring to Bill McQuillen and Jim Tebbe, the head facilitators for the SIT, and Tom Botts, who serves as overall coordinator for the SIT. “They get credit for creating the conditions that allowed it to happen,” Pierce believes.

It ultimately is a very large virtual team. Around the 38 core members are 90 more on the Employee Panel, a review team recruited as representative of the broader community in which Shell lives. Panel members, nicknamed “the spoons” because of their role in “stirring the pot” in support of the networked community, include a school superintendent, a local minister, the president of a local trucking company, and several spouses of Shell employees. This design insures that the SIT does not act in isolation. Regular reviews take place with the spoons, who in turn speak with their constituencies about the meaning of the new Shell.

The SIT provides a striking example of shared leadership at the highest strategy levels. Botts leads the initiative as principal coordinator of the effort, working closely with Pierce in her role as the liaison to the Leadership Council. The four sub-teams, including the Leadership Council itself, are responsible for answering one of the four questions; each has its own leaders and facilitators. McQuillen and Tebbe share responsibility for designing the meetings that convene the whole SIT group.4 Ed Kahn, another senior facilitator at Shell, designs and leads meetings with the spoons. The Leadership Council members also weave more strands—each belongs both to the governance team and serves as co-sponsor to one of the three other teams. As outside consultants, we also contribute leadership and content expertise on networked organizations.

“Networks are leaderful. Any virtual team that attempts to operate with one formal leader is not going to make it,” Pierce says. She points to Botts’ style of leadership as required in new organizations: He’s a learner, she says. “In the networked world, things are continuously changing so the leader with the answers has no answers. Tom continuously holds the questions not the answers.” Pierce refers to this quality as “hearing the music,” meaning that there is a new background coherence for people in networked organizations. To hear it, you have to part with the traditional trapping of power—having the single right answer. Otherwise, you only hear noise. Create questions, not simple answers, and you will excel, she believes.

In a few short months, with people continuing to work their day jobs, the SIT turns out a “Networked Community Fieldbook,5” that includes seven “enabling recommendations” to propel the new Shell to a higher level of performance:

Executive Sponsorship of the process;

Network Leadership Group comprising leaders throughout the community;

Network Learning and Support Center to help build new competencies;

People Movement meaning that job postings are fluid throughout the community;

Information technology infrastructures for communication and sharing;

After Action Review, an institutionalized learning process; and

Communities of Practice in pursuit of improved business performance.

The Leadership Council endorses and approves the recommendations upon the fieldbook’s presentation, demonstrating how well the team had managed the expectations of its stakeholders. Within a few weeks:

The Network Learning and Support Center sets up shop;

The company makes investments in developing communities of practice6 across the larger network;

The U.S. Army’s practice of After Action Reviews to evaluate all meetings is instituted, and

The building of the information infrastructure to accommodate cross-boundary work is accelerated.

Even larger changes in Shell’s operating model come to pass that following summer that are served well by the work of the SIT. Royal Dutch/Shell Group, the parent company, “globalizes” all the U.S. businesses, meaning that they become accountable directly to their global organizations. Exploration and Production, long based in Houston and New Orleans, and the heart of the Shell Oil Company’s revenue stream, for example, becomes part of Royal Dutch/Shell’s global “Exploration Production” organization. Similar changes are made in the Houston-based chemical and services organizations.7

Pierce and others believe that the work of the SIT, educating people about the power of working across more porous boundaries, helps ease the transition to the global Shell organization, which itself is grappling with the next level of planetary complexity.

“The global leaders have taken on huge accountability,” she says. “‘Think globally, act locally’8 is a snappy little phrase but what does it mean to operationalize it? Does the global team trust the local team? Is the local team able to operate with the whole in mind? It’s a very hard decision to close a local plant.”

There is no insurance policy for companies like Shell that are moving from the Industrial to the Information Age. But the investment it has made in preparing for the future is instructive for other brick-and-mortar companies. Technology and resources alone do not enable success; people do.

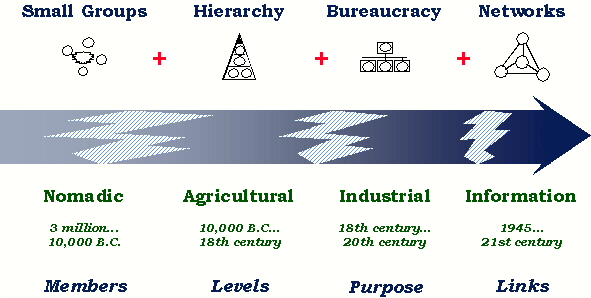

Alvin and Heidi Toffler’s 1980 book, The Third Wave, is the popular herald of a transition from the Industrial to the Information Age. It catches the crest of an idea almost four decades in the making. Now the transition is conventional wisdom. Three transformations divide human history into four great ages characterized by nomadic, agricultural, industrial, and information-based cultures (Figure 2.2).

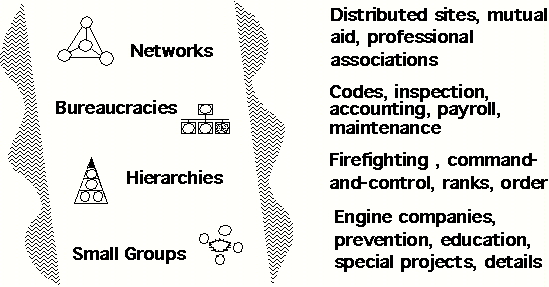

Each age has its signature form of organization.

People first hone their small group skills as hunter-gatherers. The Nomadic Era, beginning between two and three million years ago, is the source of our cultural DNA when our very early ancestors acquired the ability to speak, make tools, and configure organizations. Populations are small9 and as are families.

Hierarchy grows up with agriculture. The Agricultural Age begins 10 to 12,000 years ago, and marks a dramatic shift from the Nomadic Era. Farming and herding eventually replace hunting and gathering. Populations grow larger, cities and towns develop, and family size increases as people settle down.

The Industrial Age gives birth to bureaucracy. Beginning with ideas and technologies in the 15th century, this age becomes prominent in the 18th century dominant in the 19th, and mature in the 20th. It sees factories replace farms as the economic engine. Populations explode and urbanize, while families grow smaller. This age is the tradition out of which the new digital civilization seeks to emerge.

The Information Age brings us networks. For the last half of the century, we have been riding the turbulence of this transition as great paradigms struggle for control. The torch now has been passed. The world’s economies are information-based, electronically connected, and globally interdependent. Population is still rising, families are diversifying, and the planet has grown very small indeed.

The new virtual organizations are at once very old and very new, very small and very large. The small group virtual team is rooted in the very old and draws on skills accumulated over millennia. Networks are the very new, meeting the need for greater scope, speed, and flexibility. They grow together at the creative leading edge of epic change.

We have always—and will always—live and work in small groups. Small groups permeate every kind of organization from micro-companies and start-ups to small teams in big firms to executive committees of boards of directors.

The high-performance, information-enabled, virtual team is the Network Age version of the small group.

Each age adds its special characteristics to the previous one. Small groups have personalities and identities, and may carry the seeds of later larger organizations. As people gain status in new roles and perform tasks, they expand the vertical and horizontal dimensions of organization over the ages.

Jim is in Robin’s group. Robin is on the executive team and reports to David, the CEO, who is accountable to the board. In hierarchy, there are many status bands of low, middle, and high ranks with even more grades within them. Interestingly, this example comes from Ventro, a dot-com company, not an old-line one.

Hierarchy dramatically steepens the who’s-on-top status dimension in small groups.

As the source of legitimacy in business, owners, who have capital, also bring hierarchy. They officially crown an authority structure of executives and workers.

Hierarchy has helped people build societies among strangers throughout history. As a business grows beyond the point where everyone knows one another, hierarchy is inevitable.

Frank Reece, the founder of US TeleCenters (now View Tech), explains how quickly his company became compartmentalized. “I started with a handful of people and before we knew it, we were 350 employees, thousands of customers, and dozens of suppliers. I could see the bureaucracy growing, and I was afraid I would create a company I would hate.”

Every successful entrepreneur bemoans the loss of the “family feeling” as greater size demands structure and formality.

The Egyptian pyramids are the great organizational achievement of the Agricultural Age, the literal eternal symbol for successive ranks culminating in a pinnacle of power. A traditional organization chart brings the pyramid to mind.

Hierarchies alone are not enough. Success brings change, and simple hierarchies are notoriously unstable in the face of the unexpected. Ancient empires rose and fell as populations expanded and capacity became overextended. Boom-bust and on to bureaucracies.

Science ushers in the Industrial Age. Behind logic and the laws of motion chug the steam engine. Its cargo? Another organizational revolution: Rational bureaucracy.

Bureaucracy bulges out sideways with specialized functions, tasks, and roles.

For 300 years, corporations, nations, and organizations of all kinds become more efficient with the organizing prowess of bureaucracy. Bureaucracy, while specializing horizontally, embraces hierarchy, which controlls vertically. Together they manage much greater social and economic complexity than either could do alone. The Industrial Age is much more complicated than the Agricultural one.

But the beat of change continues, faster still. Unfortunately, when faced with continuous uncertainty and change, bureaucracy is like kudzu, the vine-like weed that spreads until it overruns everything and chokes other forms of life instead of simply connecting people in existing organizations who probably have the answer. Then the “problem” turns into a department.

So a bureaucracy grows, ever bigger, ever slower, until it just sits there, failing to innovate or change, placing drag on everything else. Finally, complexity outruns bureaucracy’s ability to organize it.

The Internet with its extraordinary spread of new connections is in a class by itself. This technological innovation has come to effect human life on a global scale in the space of a proverbial instant.

A parallel growth in connections is happening in organizations: Alliances, joint ventures, and partnerships are forming at an accelerating rate among firms of all sizes. Services are today's economy growth sector, taking advantage of the combination of people and process. Manufacturing is shrinking, as agriculture did in the Industrial Age, even as productivity grows.

Connect! It’s the organizing imperative of the Age of the Network.

In the Information Age, relationships are fundamental. Links are displacing the focus on matter, which lies inert at the center of the Industrial Age worldview.

Today we are challenged to cope with continuous global change that constantly presents us with more opportunities. Relationships—technological and human—drive the reorganization of work. Bureaucracy begins the horizontal expansion of organizations; networks take the expansion to mach speed.

What to save? What to change? Where to stay the course? When to leap ahead?

The complexity that faces 21st-century business outstrips the capacity of the accumulated wisdom of earlier ages. So we have collectively invented something new: Networks. In the Big Picture, the overall pace of change drives the next form of organization. With new technology eventually comes the ability to manage in an increasingly larger, and deeper, context.

Each age of organization builds upon and includes the past. Networks in particular are inclusive by nature. Breadth gives them resilience; diversity gives them insight; independent members keep them vibrant and learning.

In the Age of the Network, we still have hierarchies and bureaucracies, just as we continue to have farms and factories. Fire departments, typically regarded as among the least innovative of organizations, turn out to be among the most adaptive for the 21st century.10

American fire departments incorporate all forms of organization— small groups, hierarchies, bureaucracies, and networks of all sizes.

Fire fighting captures the headlines and provides riveting visuals for local TV news. The fire department springs into action as a hierarchy when battling blazes. It prepares for the crisis with command-and-control systems, practice, and training. If your home erupts in flames, you don’t want a group standing around outside trying to reach consensus on how to approach the problem. You want someone calling the shots for a highly skilled group of professionals who understand how to deal with heat, chemicals, and combustion gone out-of-control.

While fire fighting gets public attention, departments spend only a small part of their time putting out fires (in Boston, for example, only five percent). When not fighting fires, the department stays busy as a classic bureaucracy; it enforces codes, ensures pressure in water lines, updates its training, and maintains its apparatus. A chief shouting orders is of very little use if the hydrant isn’t delivering water. Here you need experts who understand pumps, pressure, and the mechanics of the city water system. Uniform codes fight fires, too.

Fire fighters are also very local. They often use networking for fire prevention, which requires education, persuasion, role models, and working directly with people in the community. School children have no patience for—or need to know about—sprinkler requirements. Their parents need to get the message about the importance of smoke detectors, fire extinguishers, a second exit from bedrooms, and "stop, drop, and roll" advice. The glamour of a visit to the local fire house and a ride on an engine leave indelible memories in children’s minds, but they don’t make children fire safe. Commitment to ongoing education does, a distinct and suitable role for networks of people working together in small groups.

Modern fire departments also forge large, inter-organizational networks for mutual aid. A group of communities agrees to act as a virtual fire department and back one another up in a particularly bad fire. Each community gains protection and reduces costs. Here local hierarchies use networks to achieve something together that they cannot accomplish alone. In this field, as in many others, people also use formal networks (e.g., trade associations) to pass legislation, share information, take on large-scale education efforts, and promote professionalism.

All kinds of organizations can learn from the local fire department. In emergencies, clear lines of authority prevail. For routine situations and environments, rules and regulations provide standards. Networks educate, innovate, motivate, and provide backup when a hierarchy-bureaucracy reaches its limits.

Fire departments—among the oldest of America’s institutions and found throughout the world—may be role models for the 21st-century organization.

A fire department provides a cumulative “geologic slice” of the evolution of organizations (Figure 2.3).

Small groups comprise the deepest layers. Hierarchy, with its chiefs and sergeants, is the next layer, imposing vertical control. Bureaucracy appears in more recent layers, bringing horizontal specialties. Finally at the top, in the verdant living topsoil, we see intensely linked, warp-speed networks. Like the fire department, most organizations today mix the forms.

Even in today’s Internet start-ups, traditional face-to-face small groups continue to be the basic work unit. At the same time, information-enabled virtual teams cross functions, deliver results to customers, and undertake special projects. All the while, the old (or even new) hierarchy continues to set strategy, maintain authority, and cope with crises with senior employees upholding the bureaucracy.

Although most people complain bitterly about them, bureaucracies, when appropriate and enabling, can be elegantly functional, high-performance entities. They standardize contractual agreements and develop common methods by which work gets done and paid for. In networks, people forge links as they cross internal functions, geographic boundaries, and even corporate lines with remarkable speed. The people in the network come from the bureaucracy and the hierarchy. Their new relationships to one another create the networks.

The most literal way that networks include earlier forms is by linking all types of organizations.

Members of a network do not themselves have to be networks.

The U.S. Intelligence Community, comprising the 14 intelligence agencies of the U.S. government—Central Intelligence Agency, National Security Agency, Defense Intelligence Agency and the like—is a network. It really has no one boss, though for administrative reasons, it reports to the Director of the CIA. Each of its constituent parts, however, is a strict hierarchy. At the global level of scientific projects, the International Gemini Project, pointing the world’s two largest optical and infrared telescopes outward to pick up the “most faint and distant galaxies,”11 is a multi-national collaboration of six governments: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, U.K., and U.S.

This diversity in the parts also pertains inside an enterprise. Departments in the same company often use different organizational forms—quite effectively if they are appropriately tuned to the environment and technology. For example, typically, marketing and product development groups are more agile in their styles than accounting and maintenance.

To repeat: All the parts of the network do not have to be the same. The 21st-century organization comprises all types: small groups, hierarchies, bureaucracies, and networks.

Today, regardless of size, most businesses exist in a global context. Asea Brown Boveri, the Swiss-based $25 billion “multi-domestic,” operates across more than 100 national borders. “We’re facing a new world where speed, flexibility, and brain power are the keys,” says Göran Lindahl, ABB’s president and CEO.12

“The world is getting smaller,” says Harry Brown, whose company, EBC Industries, has pioneered partnering with competitors. Brown’s company has just picked up a project in South America to produce discontinued parts for surplus vehicles bought in the U.S. The customer finds Brown’s firm through what Brown calls “the chain of knowledge.” Another company in their network already is supplying transmission parts. The project has caused EBC to consider a new line of business, making repair parts for old Jeeps. “Every time you open one of those doors, another one opens up,” Brown says.13 Perhaps unnecessary to say is the obvious: Neither Brown nor his partner firm travel anywhere to carry out this project.

The wave of revolutionary changes catches every business scrambling to survive and position itself to prosper as the fundamental rules of the game change—from our own Internet company to a behemoth the size of General Electric to your company—or nonprofit, government agency, school, denomination, or political party. We all are unavoidably in the storm-wracked passage to a new, expansive, information-based economy and culture.

All around us we see the future come alive as we push the frontiers of markets, technologies, and human performance. Trial and error underlie the rapidly accumulating knowledge of what works virtually.

Fortunately, the old forms of organization as they currently exist will not mire us forever. We do not have to take all that is oppressive about hierarchy and bureaucracy with us as we speed into the Network Age.

We believe that some hierarchical structure is necessary for any complex, multilevel organization. Hierarchies represent ultimate ownership control and decision making and will continue to do so. However, in the Information Age, new forms of leadership that are more participatory and diverse also emerge to fulfill these needs.

Search on the keyword “Co-CEO” and thousands of links point to companies where power is shared at the top—from Wit Capital, the first online investment bank, 14 to Ameritrade Holding Company,15 to Sony.16

As with Shell Oil Company, these companies push more decisions down and out, closer to the work and the customer. We must leave behind something to make this possible—in this case, the narrow, one-way channels of communication and decision-making and the cultures of hoarding information for power. The nature of control changes with widespread communication and knowledge. Local decision making combines with centralized information sharing in the “network-enabled” hierarchy.

Bureaucracies continue to serve as our legal guardians as specialization remains essential to cope with complexity in the Information Age. Micro-management, fortunately, will go the way of the dinosaur.

Federal Express says that its information system is more valuable than its transportation system. Employees have the power to act at every point of customer contact, supported by a tracking system that is accessible to all. FedEx is among the earliest companies to allow customers to track their own transactions.

At FedEx, bureaucracy becomes an enabling infrastructure rather than a nightmare of bottlenecks.

Some bureaucracies are being transformed rather than replaced. New relationships erupt spontaneously among the departmental boxes as connections multiply.

As an offshoot of the quality movement, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Quality Panels convene for weeklong meetings several times a year during the 1990s. There, people in the field give useful input on policy and regulations to headquarters. When government budget cuts hit in the late 1990s, quality panels are vulnerable. The panels are very expensive, entailing the high costs associated with face-to-face meetings. Travel, lodging, and meals are increasingly difficult to justify in budgets that involve personnel reductions.

So DOE has moved to “virtual quality panels” with the added benefit of increasing dialogue among the panel members. “The guy in Albuquerque never got to see what the guy in Rocky Flats had said,” explains Carol Willett, whose company, Applied Knowledge Group, facilitates the virtual panels and provides web sites for their non-real-time continuation. “It turned a sequential coordination process that took months into a network collaboration process allowing more voices to be heard in a fraction of the time and cost.”17

We all belong to many different groups simultaneously. Moving from group to group, we can travel through the ages.

A fire fighter can stride through all four ages in a single work day.

Upstairs over the station house is a small world with a kitchen, break room, and bunks where the informal small group sleeps. It’s a very placid environment—until the alarm goes off. Then the group dons its fire fighting gear, snaps into a military unit, and heads for the crisis. After the blaze is put out, the fighter gets into an inspector uniform, wearing bureaucracy to assess the damage and investigate the cause. That night, the uniform comes off and a person with a mission to save lives joins with a network of teachers and other leaders working to prevent fires in the community.

Useful, timeless basic human capabilities recur in each new age. Our life is a mosaic of past and future. Each of us, like the fire fighter, exists simultaneously in all four ages.

The postindustrial model is inclusive of old models, not a replacement for them. The laws of motion in everyday life do not grind to a halt when quantum physics overwhelm Newtonian absolutes at the dawn of the 20th century. Gravity does not reverse itself when Einstein discovers relativity.

Connectivity is exploding, yet face-to-face encounters account for most of our small-group knowledge. Historically, hierarchy, in particular, has depended on the power of personal characteristics, the power of the person, the body—the Big Guy with the booming voice and displays of power, as well as power settings, to maintain control.

It’s hard to bring physical bearing to bear when you’re communicating by e-mail. All the CAPITAL LETTERS and !@*$* characters of indignation on the computer screen can’t compare with someone on a power trip staring you down. Physical qualities and locations are less important in the ephemeral age. We are learning new, more horizontally connected, participatory ways of achieving higher levels of small-group performance.

So, alongside the old, the new. We are rediscovering ancient small-group, face-to-face knowledge. At the same time, we’re inventing some brand new skills for the geographically-diffuse groups of the future-right-now.

1 See Landmark Graphics at http://www.lgc.com/about/about.asp.

2 See Chapter 4 ? Footnote #X, for an explanation of “graphic facilitators.”

3 Networked Community field book, Shell Oil Company, March, 1998, p x.

4 We served as consultants to the SIT [include? Disclosure issue]

5 “Networked Community Fieldbook,” Shell Oil Company, March 1998.

6 See Etienne Wenger [Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity, Cambridge University Press, 1999] and HBR article in Jan 2000.

7 Shell Services International had made this move the prior year.

8 The phrase, “Think globally, act locally,” first was used by Rene Dubos, the two-time Nobel Laureate.

9 Economically Viable Alternative Green, an Australian environmental group, estimates that there were about 270,0000 people on earth about 10,000 years ago. <www.altgreen.com.Australia/population/How_many.html>

10 In regard to the structure of fire departments: For three years in the 1970s, we helped the U.S. Department of Commerce set up Americas first national fire prevention agency.

11 See “Australia to Share in ‘Heavenly Twins,’” 18 February 1998, http://hephaestus,gemini.edu/project/announcements/press/aus_press_release.html,

12 See “‘New ABB shows strong ’99 earnings, cash generation,” February 3, 2000, Press Information, http://www.abb.com.

13 Interview with Harry Brown, (insert title, company?), January 10, 2000. For more on EBS, see The TeamNet Factor, pp. 137-139, and The Age of the Network, pp. 79-85.

14 See Wit Capital, http://www.witcapital.com/company.management.jsp

15 See Ameritrade Holding Company, http://www.amtd.com/html/about5.html

16 See Sony, http://www.world.sony.com/IR/Financial/AR/1999/Management.html

17 Interview with Mike Howland and Carol Willett, 1/20/00, http://www.akgroup.com.